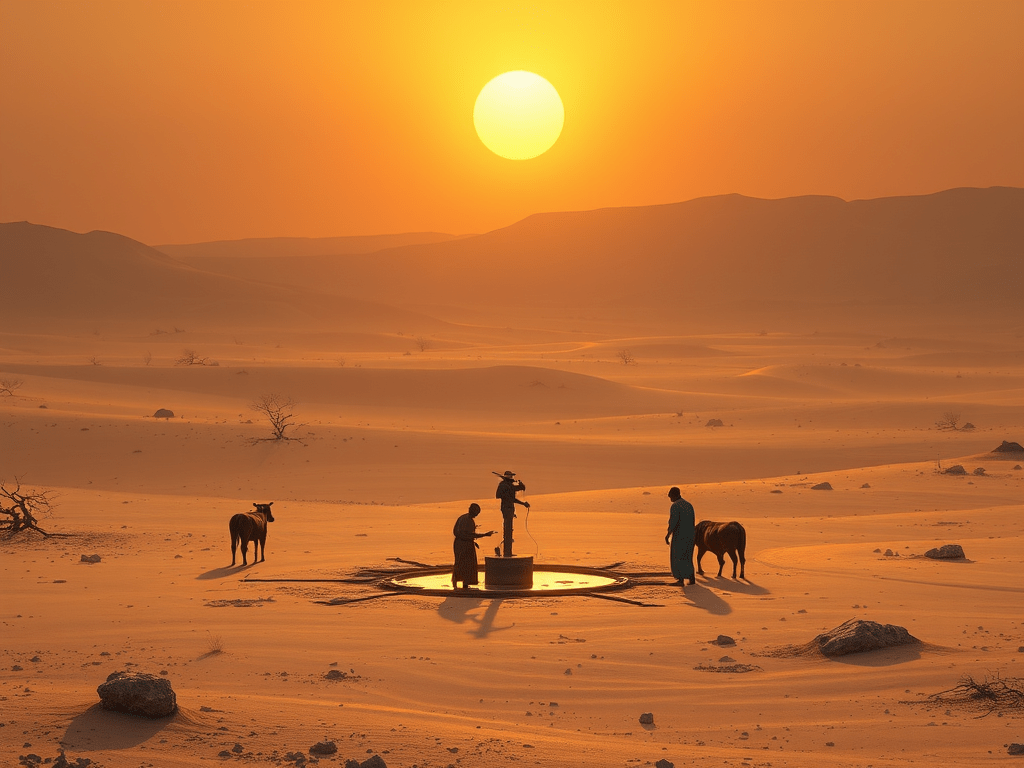

In northern Kenya, drought is no longer just a season. It is a cycle tightening its grip on land, livestock, and livelihoods.

Across counties like Marsabit County, Samburu County, and Isiolo County, the response to worsening water scarcity has been swift and visible: drill deeper.

Hundreds of boreholes have been sunk over the past decade financed by county drought funds, NGOs, politicians, and private investors. On paper, they are lifelines. In practice, they are quietly transforming who holds power in rural economies.

Because in pastoral regions, water is not just a resource.

- It is survival infrastructure.

- It is wealth.

- It is leverage.

From Communal Wells to Controlled Pumps

Historically, pastoral systems depended on shared water points and negotiated access. Mobility was the strategy: move livestock where pasture and water existed. Conflict was avoided not by abundance, but by customary agreements.

Today, that system is shifting.

Many newly drilled boreholes sit on private land or are managed by individuals with political connections. Access is increasingly monetized — per jerrycan, per herd, per visit. Those who control the pump control the grazing routes.

And when grazing routes shift, everything shifts.

A herder unable to water livestock may be forced into neighboring territory. That movement can trigger tension in areas where land boundaries are already contested.

Water scarcity becomes territorial pressure.

Territorial pressure becomes conflict risk.

The Quiet Privatization of Survival

The deeper issue is not simply drought. It is governance.

Who owns these boreholes?

- Were publicly funded water projects placed on communal land — or absorbed into private control?

- Are counties tracking how much water is extracted from fragile aquifers?

- What happens when drought emergency infrastructure becomes permanent private property?

In arid regions, groundwater recharge is slow. Over-extraction risks long-term depletion. Yet oversight of abstraction permits and monitoring capacity remains limited.

Meanwhile, informal water markets are emerging. The price of access varies. Those with cash or political alignment may fare better than those without.

A new rural hierarchy is forming — not based solely on livestock size, but on water control.

When Water Becomes a Flashpoint

Northern Kenya has long experienced resource-linked tensions. Drought intensifies them.

When a borehole restricts access, neighboring communities may interpret it as exclusion. Armed guards at private water points are no longer rare. During election cycles, promises of drilling projects can function as political currency.

Control over water becomes control over loyalty.

In fragile regions, that concentration of control carries consequences.

Water is no longer neutral infrastructure. It is an economic asset and, potentially, a security variable.

Climate Adaptation — or Economic Restructuring?

Boreholes are framed as adaptation tools. And they are. Without them, livestock losses would be catastrophic.

But adaptation is not politically neutral.

When emergency drilling expands faster than regulatory oversight, and when access becomes stratified, drought response can inadvertently restructure rural economies.

- Who profits from scarcity?

- Who absorbs the cost?

- Who decides who drinks?

These are no longer abstract policy questions. They are daily realities for pastoral families navigating an increasingly monetized water landscape.

The Question Beneath the Drought

As climate pressure intensifies, northern Kenya’s future will depend not only on rainfall patterns but on governance.

Water is being drilled deeper into the earth.

But power is rising to the surface.

The defining question may not be how much groundwater remains — but who owns the right to pump it.

Leave a comment