An Unspoken Mystery

The mere mention of FGM sparks an emotive atmosphere, especially within modern and progressive circles. The nomenclature itself offers no refuge; in any society or language, mutilation denotes harm, violence, and loss.

This is not a defense of the practice, nor an attempt to ratify it; the physical and psychological consequences of this act are well documented and deeply troubling. However, what is often missing from contemporary discourse is an honest exploration of why this practice has historically been embraced, protected, and even celebrated within certain cultural frameworks from an angle somewhat blind to the morally aligned.

Stolen Dignity in the Name of Morality

What if, playing the devil’s advocate, I attempted to illuminate not the act itself, but the symbolic meaning attached to it? What if, at the risk of communal banishment in the age of moral absolutism, I examined the cultural logic that once framed she-circumcision as a rite of dignity rather than an act of harm?

In some deeply rooted traditions, FGM was perceived as the pride of womanhood, a social gateway into respectability, moral legitimacy, and communal belonging. To deny a woman this ritual was, in many contexts, equivalent to social exile. Not because of the physical act, but because of what it represented: a passage into identity, discipline, and cultural acceptance.

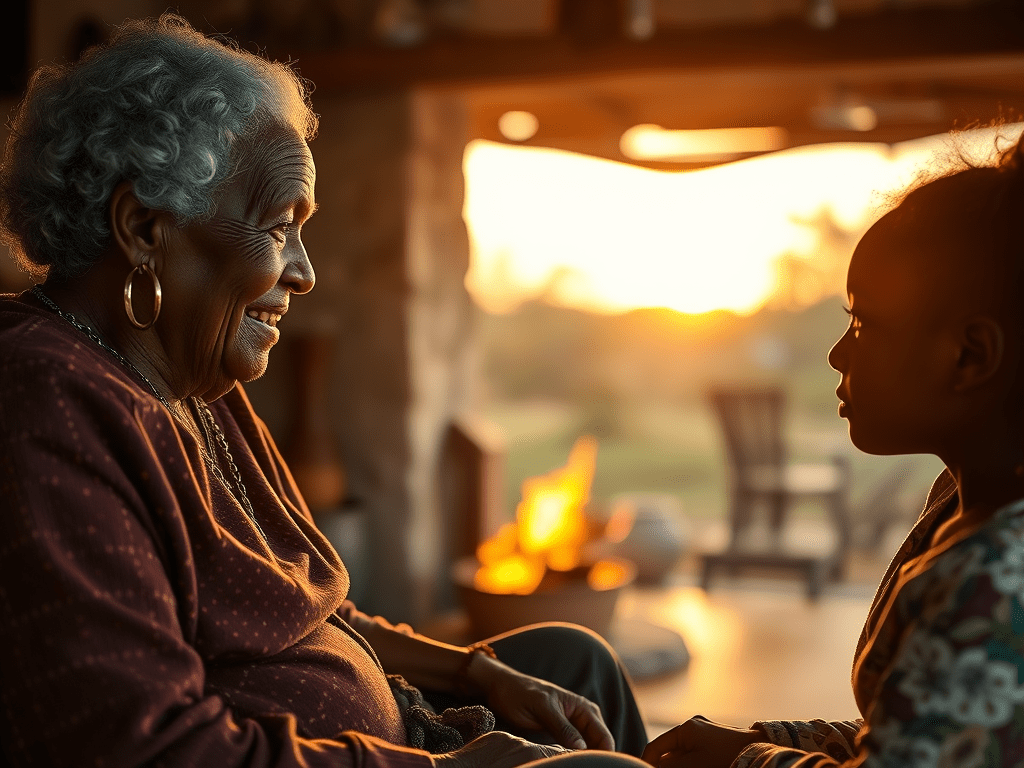

I once heard my grandmother speak of it with so much pride, the glow on her face as she narrated the custom filled the room with a strange sense of reverence. To her, the ritual paved the way for the instillation of morals in girls, especially how to be submissive wives. And while the brutality of the practice cannot be denied, I remain fascinated by the moral structure it claimed to bring to society. The act was cruel; the lessons, however, were not entirely without value. If society seeks to be right on this matter, then perhaps we must re-instill the morals without the act.

Culturally, it was a platform, but it does not have to be the only one. What if we reintroduced new platforms that provide environments where society no longer depends on archaic traditions to teach responsibility? Spaces where tolerance and wisdom about marriage are nurtured, where motherhood is taught without dehumanizing girls. Just as in some cultures where boys are taught how to be good fathers and husbands during circumcision rites, there should be a platform for the girl child that enhances her moral development while preserving her dignity.

To this day, my grandmother remains convinced that any woman who was not cut cannot hold a home. It is impossible to convince her otherwise. Perhaps because society has hidden its face from apprenticeship and mentorship, leaving a vacuum once filled by tradition. People are entitled to their opinions, and rightly so, but tradition had the right intention but the wrong execution. Let us pick the good and discard the bad, hoping that, in the end, we may cultivate resilience that comes not from female mutilation but from conscious moral formation.

We can learn without pain and stand without shame. A woman is the gateway to life; she should enjoy life and the pleasures it allows. Say no to FGM and yes to morals

Leave a comment