The Hidden Work Continues

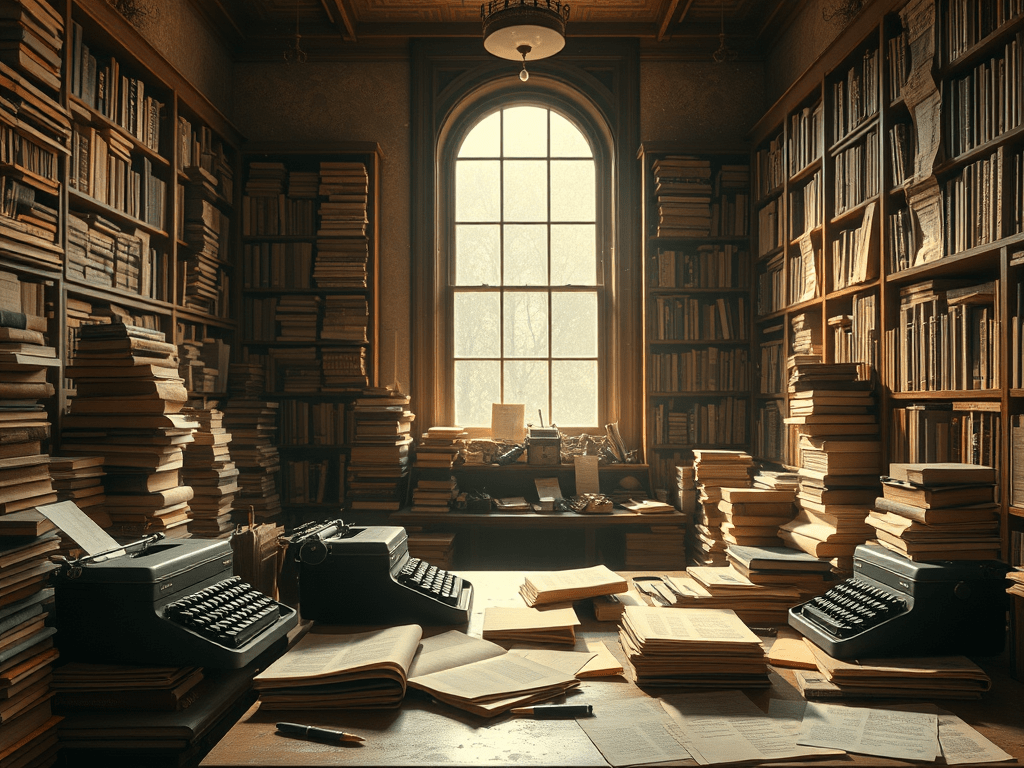

In university basements, rare-book rooms, and increasingly in digital reading interfaces, a quiet excavation is under way. Poets who once appeared in modest chapbooks, regional quarterlies, or mimeographed little magazines are being read again—not as historical curiosities, but as living craft. Their drafts, letters, marginal notes, and abandoned sequences are surfacing through digitization projects, scholarly editions, and deliberate curatorial work.

What emerges is not merely “lost” talent, but evidence of how poetic possibility was wider, stranger, and more various than the mid-century canon usually admits.

A Case in Point: Lucille Lang Day

Suggested pull-quote placement here (sidebar or breakout box):

“Each crossed-out stanza, each line restored years later, is a record of patience that changes how we read the finished poem.”

One recent example is the slow reappearance of Lucille Lang Day, an American poet whose early books (Self-Portrait with Hand Microscope, 1982; Bering Strait, 1986) circulated mainly in West Coast small-press circles. For decades her work remained visible only to specialists in ecopoetics and women’s poetry of the nuclear age.

Between 2022 and 2025, however, university archives in California and Oregon made substantial portions of her correspondence, teaching notes, and early typescript drafts publicly accessible. Readers now encounter the meticulous way she revised long-lined meditative poems into tighter, image-driven lyrics—changes that reveal a poet actively negotiating between confessional intimacy and scientific precision.

Archives as Active Reading Spaces

Suggested pull-quote placement here:

“Archives are no longer passive storage; they have become active sites of re-reading.”

Digitized manuscripts, early audio recordings, corrected proofs, and unsent letters expose the labor that publication usually conceals: the dozens of ways a line could break, the hesitation before a metaphor, the moment a poet chose restraint over excess. Seeing these decisions in real time makes craft visible again.

They also unsettle the idea of a single “finished” poem. When early drafts become searchable, we watch poems being made and unmade—sometimes over decades.

Expanding the Map of 20th-Century Poetry

Suggested pull-quote placement here:

“The canon is not a museum exhibit but a living argument, one that changes every time a new folder is opened.”

These recoveries rewrite the map of 20th-century poetry. They surface voices that geography, gender, race, class, or aesthetic allegiance kept on the margins. They show how many poets were quietly working in modes—eco-attentive, hybrid, politically oblique—that we now associate with later generations.

At several Canadian university special collections, the papers of lesser-known poets active in the 1950s–1970s—especially women and poets of color who published with micro-presses—have been processed and partially digitized in the last five years. One ongoing project has brought forward typescript versions of poems that were never printed because the journals folded or the poet withdrew the work. These drafts frequently show bolder formal experiments than the more conservative pieces that did reach print.

Why the Past Is Speaking Now

The significance is not nostalgic. These poems speak directly to the present: anxieties about ecological collapse, diasporic identity, gendered violence, the pressure of surveillance states. Reading them now creates a conversation across decades, not a lecture from the past.

Suggested final pull-quote placement (closing emphasis):

“Each rediscovered page becomes evidence that poetry has always been more plural than textbooks allow—and that the conversation is still open.”

When we bring forgotten voices back into circulation, we do not simply recover history. We enlarge the present.

Leave a comment