By Mark Onchiri

Born from Necessity

Matatus emerged in the 1960s after independence, when informal operators filled gaps left by colonial transport systems. The name comes from Swahili slang for “three,” a reference to the original fare. But it was during the economic shifts of the 1980s and 1990s, alongside the global spread of hip-hop culture, that matatus became cultural icons.

“If your matatu wasn’t flashy, you lost business,” says Brian Wanyama, founder of Matwana Matatu Culture, which documents the phenomenon. “Style was survival.”

Competition pushed owners to customize their vehicles—first to attract passengers, then to express something deeper. What began as marketing evolved into culture.

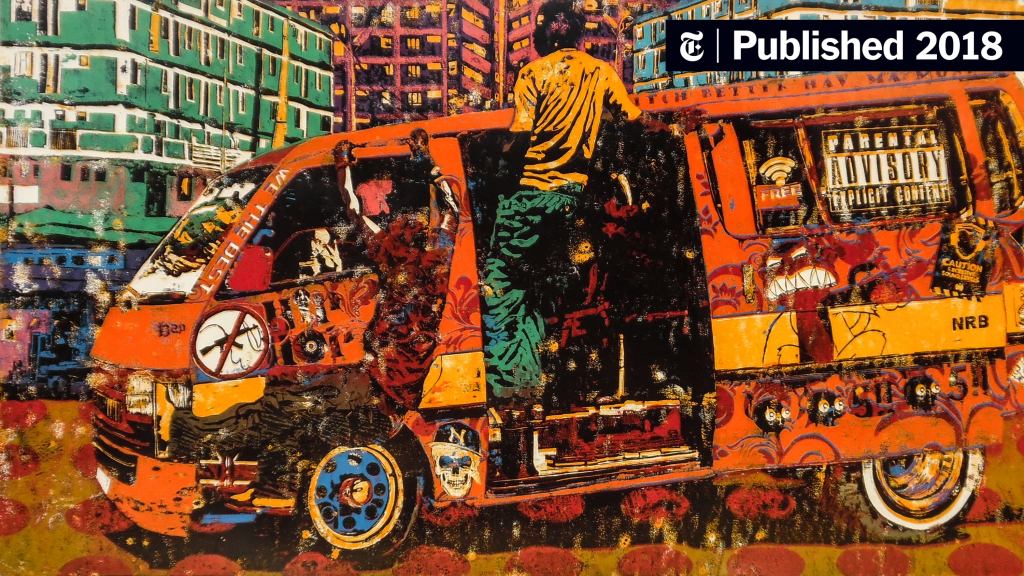

Rolling Galleries

Most matatu artists are self-taught, working from small garages in neighborhoods like Eastlands. Using spray paint, vinyl wraps, and LED kits, they layer vehicles with portraits of global icons such as Tupac Shakur or Bob Marley, alongside Kenyan musicians, political figures, and religious imagery. Neon greens and electric blues dominate. Slogans like Money Fest or God First announce ambition and belief.

Inside, custom upholstery, lighting, and sound systems create immersive environments. “Each matatu tells a story,” says graffiti artist Babel Gody, who has worked on several high-profile vehicles. “It reflects the owner’s dreams and the community’s vibe.”

Design as Defiance

Matatu culture openly defies Nairobi’s formal urban order. Much of the city’s architecture caters to elites—glass towers, gated developments—while the majority navigate congestion and informality. Matatus reclaim public space through color, noise, and movement.

“They’re museums on wheels,” Wanyama says. Unlike static galleries, matatus interact with thousands of people daily. Riders choose which matatu to board, creating a feedback loop where bold design is rewarded. Innovation is driven from the street up.

Historically, matatus have also carried undertones of resistance. During the repressive years of the 1980s, subtle graffiti and music choices became quiet forms of dissent. Today, the movement remains deeply economic. With youth unemployment above 35 percent, matatus create jobs for painters, welders, electricians, and sound technicians. Owners can invest hundreds of thousands of shillings in customization, sustaining entire micro-industries.

Veteran artist Mohammed Kartar, known as Moha, has been part of the scene since the early 1990s. “I wanted something people reacted to,” he says. His work helped shift matatus from simple portraits to full design statements.

A Culture Under Threat

Despite their cultural significance, matatus are frequently targeted by modernization efforts. Past policies sought to replace them with larger buses, viewing them as chaotic. More recently, the rollout of Bus Rapid Transit systems has raised fears of enforced uniformity.

“We shouldn’t erase this culture,” says journalist Janet Mbugua. “It’s how Nairobi speaks outside boardrooms.”

Riders agree. “The designs make the ride fun,” says Mary Njeri, a vendor I meet on a Kibera route. “Without them, it’s just another boring bus.”

The People’s Architecture

At their core, matatus represent vernacular design—creative innovation built with affordable materials and local knowledge. Typography mixes Swahili slang with English wordplay. Visuals blend global pop culture with African tradition. The result mirrors Nairobi itself: hybrid, restless, and expressive.

“Matatus are the people’s architecture,” says urban designer Naomi Mwaura. While she notes ongoing gender imbalances in the industry, she sees matatus as rare spaces where marginalized voices visibly shape the city.

As my matatu screeches to a stop downtown, bass still thumping, I step back into the street reminded that cities are most alive when creativity is allowed to spill into everyday life. In an era of increasingly uniform urban design, Nairobi’s matatus insist on color, noise, and personality—turning the ordinary act of getting to work into a statement of cultural defiance.