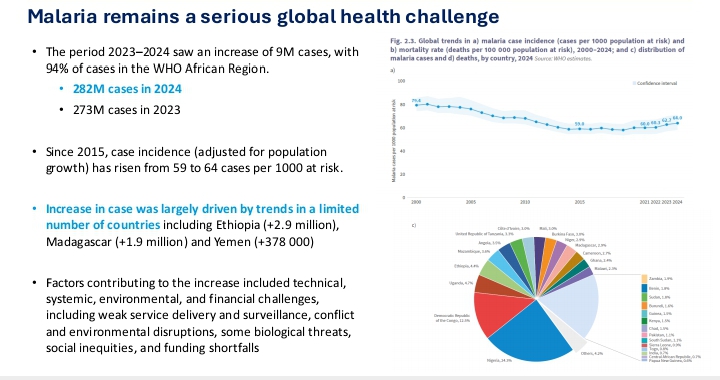

Every minute, someone somewhere dies from malaria — a disease scientists have known how to prevent and treat for decades. In 2024 alone, the World Health Organization estimates roughly 282 million malaria cases and about 610,000 deaths worldwide, with about 95% of those deaths occurring in the WHO African Region and most among young children under five years old.

(World Health Organization)

That statistic is jarring because the tools to stop malaria exist: bed nets, effective medicines, rapid tests, and even vaccines. So why does a preventable and treatable disease still kill hundreds of thousands of people every year?

The answer is not a lack of knowledge — it’s a combination of fragile health systems, inequality, biological adaptation, climate change, and chronic underfunding.

Malaria’s Biology: A Preventable Threat

Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites transmitted through the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes. Over the years, scientists have developed a suite of interventions that can significantly cut transmission and save lives:

- Insecticide‑treated mosquito nets (ITNs)

- Indoor residual spraying

- Rapid diagnostic tests

- Antimalarial medications

WHO‑recommended malaria vaccines now being rolled out in many African countries

World Health Organization

These tools work — and they have worked. According to WHO, the wider use of new prevention tools in 2024 may have prevented an estimated 170 million malaria cases and saved around 1 million lives.

World Health Organization

But the existence of tools and equitable access to them are two very different things.

Why Prevention Falls Short

Fragile Health Systems

In many malaria‑endemic countries, especially in rural areas, clinics are understaffed, poorly stocked, and distant from where people live. Even when nets or medicines are theoretically available at the national level, they often never reach the families who need them most.

Funding Gaps and Donor Fatigue

Malaria control efforts rely heavily on international support. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria provides a major portion of financing for malaria programs, but global funding remains far below what’s needed. In 2024, only about $3.9 billion was invested, less than half of the roughly $9 billion required to scale up prevention and treatment effectively. Cuts in aid from major donors also threaten progress, with advocates warning that reduced funding could lead to millions of additional cases and deaths over the next decade.

The United Nations Office at Geneva

The Guardian

Resistance and Biological Challenges

The malaria parasite and the mosquitoes that carry it are adaptive. Resistance to front‑line antimalarial drugs and insecticides has been documented in many parts of Africa, forcing health officials to constantly update treatment and prevention strategies.

World Health Organization

The Inequality That Drives Malaria

Malaria is not just a biological disease — it’s a disease of social and economic inequality.

Poor families may share a single bed net among many people, decreasing its effectiveness.

Seasonal workers and displaced populations often lack consistent access to prevention tools.

Education gaps and misinformation can discourage timely treatment.

In sub‑Saharan Africa, where most malaria cases occur, communities with the weakest health infrastructure are often the most vulnerable.

Signs of Real Progress

There are reasons for hope.

Some countries have dramatically reduced malaria deaths by combining strategic investments and community outreach. For example:

- Since 2000, global malaria interventions have averted an estimated 2.3 billion cases and approximately 14 million deaths worldwide. World Health Organization

- Dozens of countries — like Egypt, Cabo Verde, and Timor‑Leste — have been certified malaria‑free by WHO after sustained efforts. World Health Organization

- Malaria vaccines approved by WHO are now part of routine immunization in at least 24 countries, protecting millions of children. World Health Organization

- Even with progress, however, malaria remains a heavy burden. In 2024, the global death toll rose slightly compared with previous years, and resistance continues to threaten gains. World Health Organization

Climate Change and New Frontiers

Climate change is expanding mosquito habitats into places that were once low-risk, complicating prevention strategies and placing more populations at risk. Extreme weather, flooding, and changing rainfall patterns make it harder for health systems to maintain consistent malaria control.

World Health Organization

Research into new prevention tools — from next-generation bed nets to advanced vaccines and genetically modified mosquitoes — offers future promise, but equitable distribution remains the greatest challenge.

A Disease of Equity and Policy

Malaria’s persistence highlights a stark truth: it’s as much a policy and equity challenge as a medical one.

Ending it will require:

- Sustained investment in local health systems and community health workers

- Broader access to vaccines, diagnostics, and treatments

- Continued innovation against drug and insecticide resistance

- Political commitment and global cooperation to maintain funding and distribution

These are not just scientific imperatives — they are matters of social justice.

Conclusion

Malaria still kills hundreds of thousands each year not because we lack the tools to stop it, but because those tools are unevenly distributed, underfunded, or undermined by resistance and structural inequality. Turning the tide against malaria will require a combination of scientific innovation, robust health systems, and a collective resolve to ensure that no community is left unprotected.

Leave a comment