By Mark Onchiri

In Nairobi, creativity often begins where resources are limited. For Cyrus Kabiru, this truth was shaped early in life. Born in 1984 and raised near the Korogocho dumpsite, one of the city’s largest informal settlements, Kabiru grew up surrounded by discarded objects that many people learned to ignore. Over time, those discarded materials became the foundation of his artistic vision.

Korogocho exposed Kabiru to a constant cycle of reuse and survival. His father, a repairman, rarely threw broken items away. Damaged spectacles were fixed using salvaged parts, teaching young Kabiru that value is not defined by newness but by imagination. Although his father hoped he would pursue engineering, Kabiru was drawn to art—experimenting freely and learning by observation rather than formal instruction.

Self-taught and instinctive, Kabiru developed an artistic process rooted in curiosity. He often walks through Nairobi collecting objects others have abandoned, allowing the materials to guide his ideas. He describes this as a conversation between artist and object, where form emerges naturally rather than through rigid planning. Kenya’s diverse landscapes—from forests and deserts to lakes and coastlines—also play a role in his creative reset, offering balance between urban chaos and reflection.

C-Stunners: Art, Identity, and Futurism

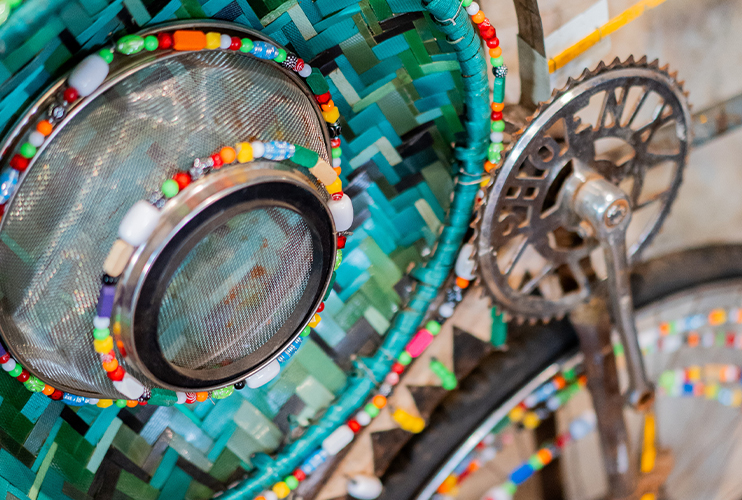

Kabiru’s most recognized body of work is the C-Stunners, a series of sculptural eyewear made from recycled materials such as scrap metal, electrical components, bottle caps, computer keys, and wire. What began as playful experimentation evolved into a powerful artistic language blending sculpture, fashion, photography, and performance.

The C-Stunners are not merely objects for display. Kabiru wears them himself, photographing the pieces as self-portraits. By placing his own image at the center of the work, he challenges ideas of identity, visibility, and authorship. The eyewear is often futuristic and unconventional—sometimes humorous, sometimes unsettling—yet always intentional.

Through this series, Kabiru engages with Afro futurism in a grounded way. Rather than imagining distant worlds, he constructs futures from local materials and lived experience. His work questions who gets to imagine the future and how African creativity is represented within global narratives.

Objects That Carry Memory

Beyond eyewear, Kabiru’s practice extends to sculptures inspired by bicycles, radios, and everyday machines common in Kenyan life. One of his notable series, Black Mamba, draws from the iconic Indian-made bicycles that once dominated Kenyan roads. For Kabiru, the bicycle symbolizes movement, childhood memory, and the rhythms of urban life.

In works such as Miyale Ya Blue, created from electronic waste and shaped like a radio, Kabiru explores themes of transmission, ancestry, and time. The title, drawn from the Swahili word for “rays,” suggests sunlight and spiritual connection. These objects feel both ancient and futuristic, bridging technology and tradition.

Through these pieces, Kabiru quietly critiques consumer culture and environmental neglect. By transforming waste into art, he invites viewers to reconsider what they discard—and what stories those objects may still carry.

Global Recognition, Local Roots

Kabiru’s work has gained international recognition, with exhibitions in major institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, the Saatchi Gallery, and the Mori Art Museum. His inclusion in landmark exhibitions such as Before Yesterday We Could Fly at the Met positioned him within global conversations on Afro futurism and contemporary African art.

Despite this visibility, Kabiru remains deeply rooted in community. He has established studios in Nairobi offering free art lessons, particularly to young people with limited access to creative education. What began as informal gatherings grew into spaces for learning, experimentation, and self-expression.

Kabiru also mentors emerging artists and reinvests exhibition proceeds into educational initiatives. His approach reinforces a belief that creativity should remain accessible and that success carries responsibility.

Reframing Innovation

Cyrus Kabiru’s journey challenges conventional ideas about innovation, art, and African creativity. His work does not romanticize hardship, nor does it separate imagination from reality. Instead, it shows how intelligence, adaptability, and vision can flourish under constraint.

From Nairobi’s dump sites to the world’s leading galleries, Kabiru’s story reminds us that the future is not always built from new materials. Sometimes, it is shaped quietly from what others leave behind—and by those who dare to see differently.

Leave a comment