At the break of dawn in Busia County, trucks idle near the border long before Customs officers arrive. Some are empty while others are fully loaded. By midday, sugar that technically does not exist will be stocked in wholesale stores across western Kenya. It’s paper trail dissolved without a trace somewhere between Uganda, Tanzania, and the Indian Ocean.

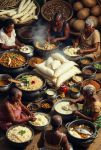

This sugar will subsequently end up everywhere across the spectrum in tea cups, soda bottling plants, school canteens, and street stalls retailing cheaper than locally milled cane, cheaper than milk, and cheaper than protein. Nobody will question where it originated from, and everyone will consume it in silence. This is how addiction moves when it is politically protected.

Policy failures by design

Kenya’s sugar crisis has been officially acknowledged for decades. Task forces are formed. Reports are written. By the end of the day, the recommendations are shelved.

State-owned mills like Mumias, Nzoia, Sony, and Chemelil have collapsed repeatedly under debt, mismanagement, and political interference through patronage. Each collapse triggers the same response: bailouts without reforms, leadership changes without accountability, and endless suffering to the local cane farmer. https://www.capitalfm.co.ke/business/2025/09/govt-to-reopen-four-leased-state-owned-sugar-factories/

Meanwhile, import controls are inconsistently enforced. Temporary duty waivers are issued “to stabilize supply,” often during election cycles. Safeguards get lifted, then reinstated, then lifted again. The result is a regulatory fog offering perfect conditions for cartels to thrive. The sugar policy is not failing accidentally. It is failing intentionally and predictably.

The Corporate Layer

Multinational food and beverage companies operating in East Africa rely on cheap refined sugar, The margins heavily depend on it. While they do not publicly engage in smuggling. Their demand creates pressure for low-cost supply in a broken regulatory environment such as this.

At the same time, large firms import sugar for “industrial use”, but it quietly leaks into retail markets. Once repackaged, its origin becomes irrelevant to the industry players: sugar is sugar.” No brand names appear on the sacks, and accountability evaporates.

The trade routes no one wants to map

Illicit sugar flows into the region through three primary corridors:

- Uganda – Western Kenya route

Sugar enters Kenya from Uganda sometimes legally, at times under-declared, then spreads into Kisumu, Kakamega, Bungoma and beyond

- Tanzania – Southern corridor

Imports arrive through Dar es Salaam, are rerouted inland and cross into Kenya via Namanga or smaller unofficial border crossing points.

- Coastal entry via Mombasa

Under-invoiced consignments land at the port, declared as industrial sugar or other commodities, then disappear into the domestic circulation without a trace.

These routes are well known to traders, transporters, and the regulators. Enforcement is selective as disrupting it would disrupt powerful interests. https://nation.africa/kenya/business/firms-on-the-spot-for-diverting-industrial-sugar-to-domestic-use-1075940, https://nation.africa/kenya/business/firms-on-the-spot-for-diverting-industrial-sugar-to-domestic-use-1075940

Cheap sugar, expensive bodies

Across the major Cities of Nairobi, Kisumu and Mombasa, sugar is now structurally embedded in daily life. A half-litre of soda costs less than fresh milk. Sweet tea is the cheapest “meal” available of the populace. Doctors see the outcomes. Diabetes rates have risen, and renal units are overflowing with clients. Amputation procedures have become a routine practice. Yet public health campaigns focus on personal responsibility: eat better, exercise more, reduce sugar. This advice blatantly ignores the economic reality. You cannot “choose better” when it is priced out of reach for most people.

Who gets shielded

No sugar importer has faced sustained arrest and prosecution proportional to the damage caused by their actions. No political figure has been held accountable for the policy chaos that enables the illicit to flourish. No serious restrictions have been placed on sugar, leading to its heavy marketing to children. Instead, the narrative has been turned around to blame the consumers of sugar. This is the oldest vice strategy in the book: to normalize supply and individualize harm,

Why sugar is untouchable

Sugar survives scrutiny as it sits at the intersection of culture, commerce and politics. It is tied to tea, East Africa’s most intimate daily ritual. It is linked to rural livelihoods that politicians fear to destabilize it. It is embedded in multinational supply chains, which governments depend on for tax revenue and investment optics.

Challenging sugar means challenging comfort, votes and profit at the same time; a risk no one is ready to undertake. Few governments have gone down that path.

The dangerous Illusion

The most dangerous aspect of sugar in East Africa is not consumption, it is denial. Sugar is treated as a neutral and even benevolent product: a small pleasure in hard times, and a harmless indulgence, yet with extensive ramifications. History shows that the most destructive vices are the ones society refuses to name, and sugar is at the core of this destruction.

Until sugar is regulated with the seriousness applied to alcohol, tobacco, or narcotics and other substances, until trade routes are mapped and accounted for, policies stabilized, and corporate demand confronted, East Africa will continue to sweeten its struggles and absorb the cost in blood, limbs and debt. It is a story about power, protection, and a region quietly addicted, with the full knowledge of those who benefit from its illicit trade practice. https://thecommonwealth.org/news/blog-kenyas-first-ever-national-strategy-combat-illicit-trade-boosts-countrys-big-4-agenda, https://www.foodbusinessmea.com/kenya-sugar-board-launches-nationwide-crackdown-on-illegal-sugar-trade/

Leave a comment