You walked into the outpatient department feeling only moderately unwell. You had a stubborn headache. There was a little nausea. Maybe you were experiencing the beginnings of a fever. You signed the register at 8:17 a.m., took your number (147), and settled into the sea of plastic chairs. By the time the nurse finally shouts “One-four-seven!” at 2:43 p.m., you are convinced you have malaria, tuberculosis, a brain tumor, and possibly Ebola.

Welcome to the Kenyan public-hospital waiting bay: unofficial medical school, anxiety factory, and—sometimes—actual source of a brand-new illness.

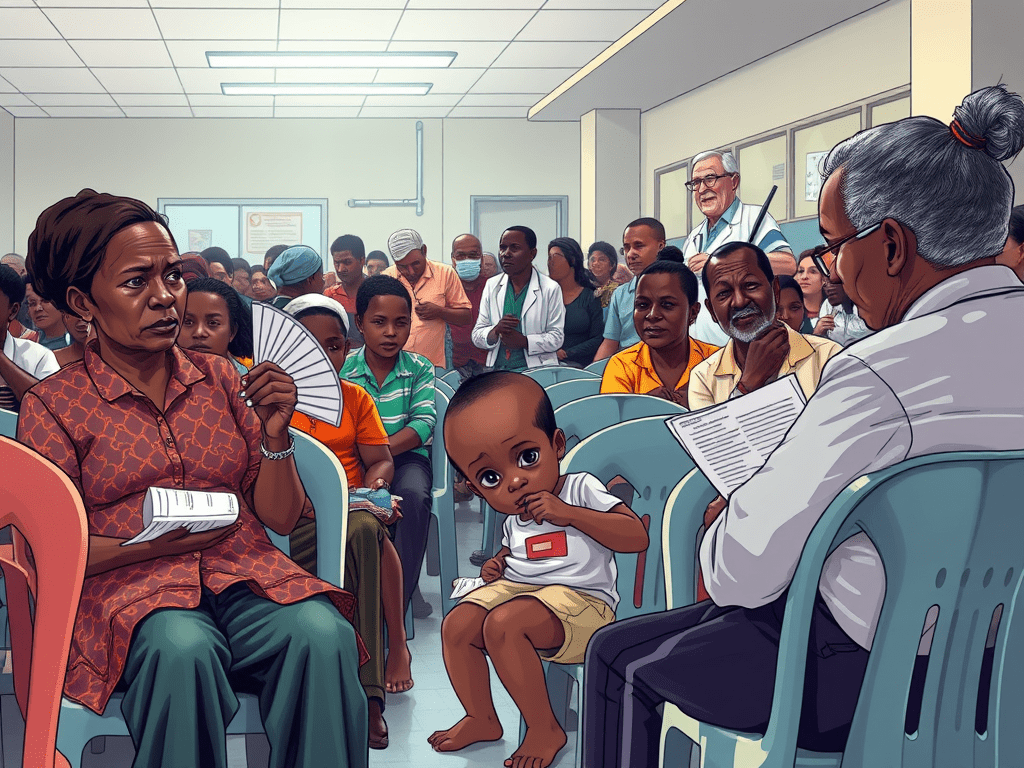

Scene Setting: The Familiar Chaos

You know the choreography by heart. This happens if you have ever been to a Level 5 or Level 6 hospital in Kenya. The benches are packed so tightly that your neighbour’s elbow becomes an involuntary blood-pressure cuff. Someone’s toddler is licking the chair leg. An elderly mama fans herself with a lab-request form. She is narrating, in full detail, the colour and consistency of her stool to anyone within a five-metre radius. The man opposite you has been coughing since Jomo Kenyatta was president. The air smells of Dettol, sweat, unwashed cardigans, and despair.

There is no privacy. There is no quiet. And there is definitely no escape from the amateur diagnostic network that springs to life the moment you sit down.

Phase 1: Symptom Comparison (5–30 minutes)

It starts innocently. You glance around to see how bad everyone else looks—purely for bench-marking purposes, of course.

- The lady clutching her abdomen and rocking back and forth? Clearly appendicitis.

- The young man whose legs are swollen like balloons? Kidney failure.

- The child with the barky cough? Whooping cough. Definitely whooping cough.

Within ten minutes you have mentally ranked every patient by severity. You feel briefly relieved—your headache seems trivial—until you notice the quiet teenager whose eyes are yellow as ripe mangoes. Jaundice. Hepatitis. Liver cancer. And now your own eyes feel… yellowish? You tilt your phone camera to selfie mode for confirmation. Verdict: definitely dying.

Phase 2: The Expert Consultation Network (30–90 minutes)

Kenyans do not suffer in silence. We diagnose loudly and generously.

“Unasema unaumwa kichwa tu? Hiyo ni pressure. Ulipima pressure?” “Eeeh, mimi nilikuwa tu na kiharusi kidogo tu, sa ile homa ya dengue ilinipatia.” “Hii cough yangu started after I was bewitched in the village…”

Every waiting room includes at least one retired nurse. There’s always one pharmacy attendant. You’ll also find one person who “almost became a doctor but life happened.” They hold court. Prescriptions are exchanged like business cards. Someone will swear that cinnamon and ginger cure everything from diabetes to heartbreak. By the time you leave, you have a shopping list of herbs. You have developed a new fear of hypertension. You also receive vague instructions to “just buy amoxicillin from the chemist.”

Phase 3: Google Becomes Your Lab Technologist (Hour 2+)

Battery at 40%, but WebMD, Mayo Clinic, and random WhatsApp forwards are now your primary care providers. You type your original symptom plus everything you have observed in the room:

- headache + yellow eyes

- headache + swollen legs + cough

- headache + child licking chair

Top results: lymphoma, HIV, or “See a doctor immediately.” Helpful.

Phase 4: The Actual Medical Risk

While your mind is busy inventing diseases, your body might be acquiring real ones. Poor ventilation contributes to this. Hours of recycled air make things worse. The sheer density of coughing, sneezing humans turns many waiting areas into perfect little petri dishes. Respiratory infections, flu, even measles outbreaks have been traced back to crowded OPD waiting rooms. One study at a large referral hospital found something noteworthy. Patients who waited more than four hours were more likely to leave. They often left with a new respiratory symptom. They were significantly more likely to have one than when they arrived.

In maternity waiting areas, it’s the same story: women in labour sit next to women with infections. Newborns are wrapped in the same shuka that was on the bench five minutes earlier.

The Psychological Toll

Doctors call it “medical student syndrome” when med students convince themselves they have every disease they study. In Kenya we have “waiting-room syndrome.” Prolonged waiting, uncertainty, and exposure to visible suffering trigger anxiety that manifests as physical symptoms. Your heart races (is this a heart attack?), your palms sweat (malaria?), your stomach churns (ulcers? cancer?).

By the time you finally see the clinician, you present with ten new complaints that weren’t there at 8 a.m. The doctor—overworked, behind by 80 patients—scribbles “anxiety” or “viral URTI” and moves on. You leave clutching a packet of paracetamol and the firm belief that the system is trying to kill you.

Can Anything Be Done?

Some hospitals are trying. They use appointment systems and better triage. They create separate areas for infectious cases. Television screens display health education (that everyone ignores). They even use simple fans to move the air. Private facilities with comfortable seating, Wi-Fi, and coffee stations have largely solved the problem—by pricing most of us out.

But in the places where the majority of Kenyans seek care, the waiting room remains many things. It is a test of endurance. It serves as a masterclass in communal suffering. Too often, it becomes an unaccredited medical degree.

Final Diagnosis

Next time you find yourself in that plastic chair, earphones in, staring determinedly at your phone to avoid eye contact with the gentleman whose leg wound is definitely gangrenous, remember this:

The waiting room is not just where you wait for a diagnosis. Sometimes, it is the diagnosis.

Bring a mask. Bring water. Bring patience. And whatever you do, do not start comparing symptoms. Your headache was probably just dehydration. Until you sat down.

Leave a comment