In the smoky glow of Nairobi’s dial-up cyber cafes, a quiet band of women learned to code, troubleshoot, and dream big—planting seeds for Kenya’s booming tech ecosystem long before anyone whispered “Silicon Savannah.” Their stories remind us that innovation often starts with a shared keyboard and a pot of tea.

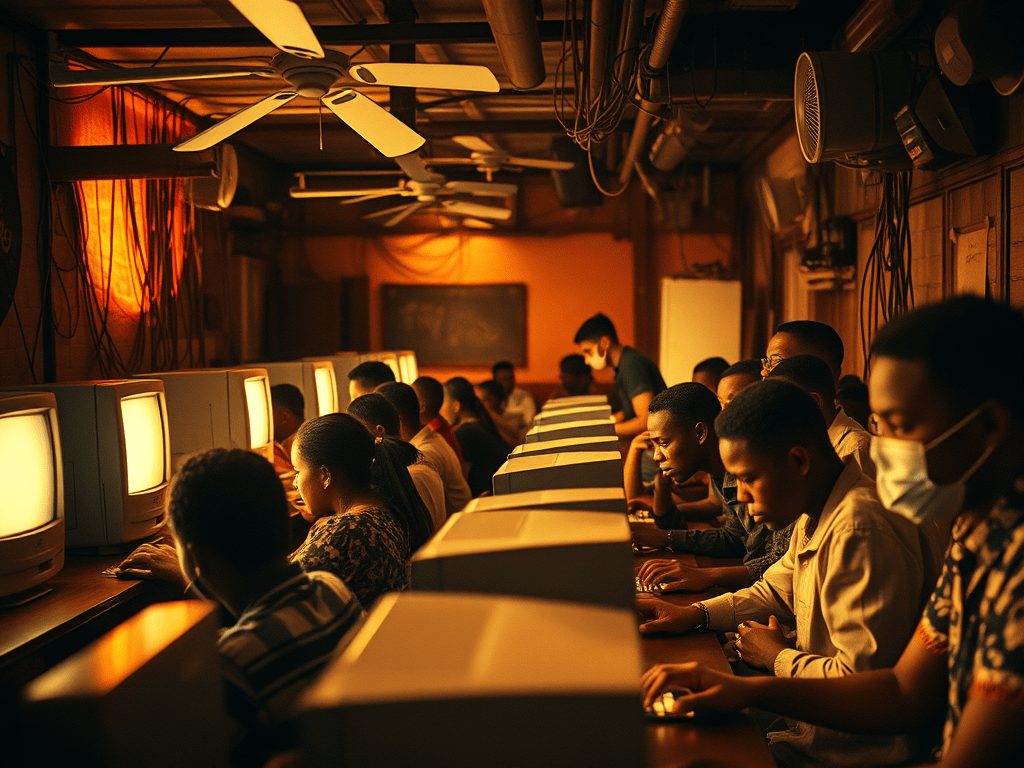

It’s 1997, and the air in downtown Nairobi hums with the screech of modems connecting to a world just beyond the horizon. No smartphones, no fiber optics—just clunky PCs with CRT monitors crammed into tiny rooms that smell of printer ink. These were the cyber cafes, Kenya’s first portals to the internet, born from a single leased line in 1995 that trickled data at a snail’s pace. For a few shillings an hour, anyone could log on. But amid the students cramming for exams and traders checking commodity prices, a handful of women were doing something revolutionary: teaching themselves to code, and learning emailing.

These forgotten women in Nairobi’s 1990s cyber cafes weren’t chasing headlines. They were secretaries squeezing in late-night HTML lessons, market vendors debugging scripts on borrowed machines, and university dropouts piecing together their first websites. Their work laid the quiet foundation for what we’d later call Kenya’s Silicon Savannah. Let’s rewind and meet them.

The Dial-Up Dream: Birth of Nairobi’s Cyber Cafes

Kenya’s internet story kicked off modestly. A home computer then cost more than most salaries. Internet lines were slow and scarce. In 1995, the Kenya Posts and Telecommunications Corporation flipped the switch on the country’s first connection—a 64 Kbps line that felt like magic to early adopters. By the late ’90s, cyber cafes sprouted like roadside kiosks, offering escape from the city’s chaos. They simply bridged the gap. Places like Africa Online and Nabuka Cyber Cafe became hubs, charging KSh 50 for 30 minutes of glory.

The vibe? Electric yet frustrating. You’d hear the modem’s warble—that iconic handshake with a distant server—followed by the thrill of a loading page. Fans whirred against the heat, keyboards clicked like Morse code, and power outages were just part of the rhythm. For women, these spots were double-edged: safe-ish public spaces to learn basic website building for small businesses, type, emailing, etc., but often eyed with suspicion in a conservative society. Tech fields felt male-dominated even then. Many honed skills that would later fit into formal tech jobs. In short, cybercafés were classrooms and community centers.

Yet they showed up. Why? Opportunity. Formal computer classes were rare and pricey, but a cafe booth was democratic. One regular, a fictionalized echo of real pioneers like those in early Nairobi forums, might have been Amina, a 25-year-old clerk who balanced ledgers by day and built personal sites by night. “It was our secret club,” she’d say with a chuckle, recalling how she’d swap floppy disks of free code with other women, dodging the cafe owner’s watchful eye on “idle chatting.”

These cafes weren’t just about email; they sparked skills, but it mattered. Women tinkered with basic programming—think early JavaScript for simple forms or Perl scripts for chatbots—fueling a grassroots tech curiosity that rippled outward because they taught their neighbours.

Hidden Heroes: Women Who Coded in the Shadows

Fast-forward to the early 2000s, when those cafe nights bore fruit. Enter figures like Susan Oguya, whose story mirrors countless unsung ones. Growing up in rural western Kenya without a home PC, Susan got her first experience at 15 via her uncle’s setup. By university, she was one of just 10 women in an 80-person IT class, facing professors who dismissed her questions. But cyber cafes? They were her lifeline. There, she honed skills that led to M-Farm, an app empowering 7,000 farmers to check crop prices via SMS—bypassing shady middlemen.

Susan wasn’t alone. Apollo Mwangi, another trailblazer, blogged from cafe connections in the mid-2000s, rallying coders for Ushahidi after the 2007 elections. Her call birthed a crisis-mapping tool now used worldwide. And don’t forget the market women of the ‘90s: shunned by banks, they drove mobile money’s rise, proving women’s instincts shaped fintech before it had a name.

These women coded between life’s interruptions—babies on laps, market runs, and power flickers. Their tools? Pirated Windows 95 discs and online tutorials that loaded for 20 minutes. No venture capital, just grit.

Early e-commerce sites for local artisans, community forums that amplified women’s voices, and the sheer proof that East African women could hack the digital divide.

Not every story was triumphant. Many faced harassment in male-heavy cafes or juggled family expectations that viewed coding as “unladylike.” Still, their persistence flipped scripts, inspiring groups like Akirachix, founded in 2010 by Linda Kamau to train hundreds of girls.

From Cafes to Code: How They Built the Foundation

What did these efforts yield? A tech ecosystem rooted in real needs. While Silicon Valley chased pets.com bubbles, Nairobi’s women coded for survival—affordable apps for remittances and health trackers for remote clinics. By 2010, Kenya boasted over 200 startups, many tracing lines back to those cafe keyboards.

Cyber cafe coders influenced M-Pesa’s 2007 launch, which now handles 50% of Kenya’s GDP. Women’s early mobile savvy—texting prices from stalls—paved that path. And in education? Bootstrapped tutorials from cafes evolved into today’s iHub meetups.

Echoes in the Cloud: Their Lasting Legacy

History often remembers founders and launches. It forgets the people who built skills first. The women in Nairobi’s cybercafés did not always become CEOs. Yet their knowledge fed the system. They tested tools, trained neighbors, and kept small businesses moving online.

Today, as Nairobi’s Konza Techno City rises, it’s easy to forget the cafe hum that started it all. Yet these women’s influence lingers—in the diverse teams behind Twiga Foods or the mentors at KamiLimu, Chao Mbogho’s program bridging university gaps. They’ve shown tech isn’t neutral; it is shaped by those who show up first.

Nairobi’s cyber cafes did more than provide internet by the hour. They planted seeds. Women in those rooms learned, taught, and held local digital life together. Their work helped shape Kenya’s later tech rise. At the same time, gaps remained. Many never got formal recognition or steady pay. That omission is still visible. Fixing it means better pay, clearer career paths, and honoring informal learning.

Kenya’s tech boom is a win, but it owes a debt to these overlooked architects. We’ve gained speed and scale but lost some of that raw, communal spark. Progress demands inclusion from day one, or we risk repeating old divides.

Leave a comment