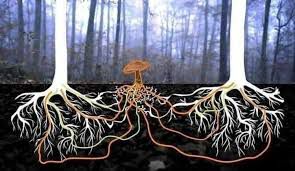

The Underground Nervous System

Beneath the serene forest floor, an intricate conversation is always unfolding. Tree roots extend and entwine with delicate white threads of fungi, forming mycorrhizal networks that link the woodland like an underground nervous system. Through this symbiotic web, trees exchange sugars for nutrients, dispatch distress signals, and even favor their genetic kin, fostering a communal resilience that defies our traditional view of plants as isolated entities.

Revolutionizing Our View of Forests

For generations, we perceived trees as silent sentinels, rooted in solitary existence. That narrative shifted with the pioneering research of forest ecologist Suzanne Simard at the University of British Columbia. In groundbreaking experiments dating back to the 1990s, Simard demonstrated how trees transfer carbon and essential nutrients via fungal hyphae. When a mature tree faces injury or decline, it often channels its stored energy to nearby seedlings, bolstering the next generation and ensuring the forest’s longevity.

The Wood-Wide Web in Action

This subterranean infrastructure, popularized as the “wood-wide web” in a 1997 Nature article, evokes a sense of wonder, but its mechanics are grounded in science. Fungal filaments function like natural conduits, shuttling water, nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon along source-sink gradients, where resources flow from abundance to need. Yet, the concept is not without controversy; recent debates in the scientific community question the extent of “communication” and altruism, arguing that some interpretations anthropomorphize passive processes. Simard and her colleagues have responded, emphasizing empirical evidence from field studies that show directed transfers and adaptive benefits.

Kin Recognition and Defense Strategies

Even more intriguing is the apparent selectivity in these interactions. Simard’s team has shown that “mother trees”, towering elders, prioritize nourishing their own offspring over unrelated saplings, suggesting a form of kin recognition mediated by chemical cues or fungal partners. Other research reveals proactive defense: When herbivores assail one tree, connected neighbors ramp up production of protective compounds like jasmonates before the threat arrives, effectively “warning” the community through the network.

Beyond Human Language

If this resembles communication, it is a far cry from human dialogue, lacking brains, nerves, or conscious intent. Scientists caution against over-anthropomorphizing, yet the coordination prompts profound questions: What constitutes intelligence in the natural world? How do these non-neuronal systems process and respond to information?

Why It Matters for Conservation

Grasping this hidden network extends beyond poetry; it is crucial for conservation. As deforestation, soil degradation, and climate change fragment these fungal systems, forests become more vulnerable, losing their capacity to share resources and rebound from disturbances like droughts or pests. Viewing woodlands as interconnected societies rather than mere timber stands could revolutionize protection strategies, prioritizing biodiversity and soil health to preserve these vital lifelines.

A Silent Symphony Beneath Our Feet

The next time you wander through the woods, take a moment to listen not with your ears, but with awareness. Below the leaf litter and soil, an ancient exchange of sugars, signals, and sustenance persists, sustaining forests for eons and reminding us of the profound interconnectedness of life.

Leave a comment