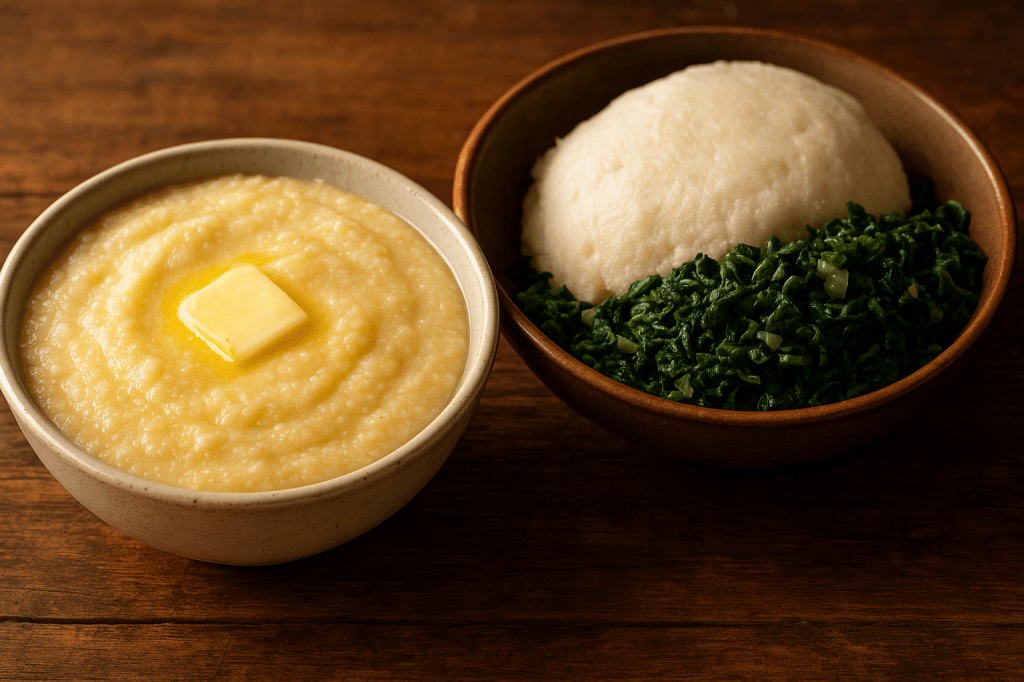

The steam rose in lazy curls from the bowl of grits placed before me in a dimly lit diner in rural Georgia, its creamy white surface dotted with a pat of melting butter. As I scooped up that first spoonful, smooth, slightly gritty, and warming from the inside out, it transported me straight back to my grandmother’s kitchen in Nairobi. There, ugali reigned supreme: a dense, moldable mound of maize flour porridge, shaped by hand into scoops for dipping into stews. The textures mirrored each other, as did the quiet ritual of the meal, a moment of pause amid the chaos of life. Two dishes, separated by oceans and histories, yet bound by the simple alchemy of corn and resilience.

Grits, that quintessential Southern staple, trace their roots to the Indigenous peoples of the American Southeast, particularly the Muskogee tribes who ground corn into a porridge-like sofkee as early as the 16th century. European settlers adopted the technique, but it was enslaved Africans in the antebellum South who elevated it, infusing it with flavors from their own heritage while adapting to the harsh realities of plantation life. Born from necessity—cheap, filling cornmeal that sustained laborers through grueling days, grits evolved into a symbol of Southern pride, echoing the resourcefulness of Black cooks who turned meager rations into soul-nourishing comfort.

Across the Atlantic, ugali tells a parallel tale. Maize arrived on Kenya’s shores via Portuguese traders in the 19th century, quickly supplanting traditional grains like sorghum and millet to become the backbone of East African diets. In pre-colonial times, similar porridges fueled communities, but ugali as we know it today embodies Kenya’s communal spirit: a staple shared at family gatherings, celebrations, and even among elite marathoners who credit its simple carbs for their endurance. It is unpretentious boiled water and maize flour, stirred vigorously into a firm dough, but profound in its cultural weight, representing resilience amid colonial commodification and modern challenges like food security.

What binds ugali and grits is not just the shared ingredient of corn, introduced through global trade routes that reshaped continents. It is their kinship as maize-based porridges, akin to African staples like South African pap or Zimbabwean sadza, which mirror grits in texture and purpose. Through the African diaspora, these dishes carry echoes of transatlantic journeys: enslaved people brought knowledge of grain porridges to the Americas, where they fused with Indigenous practices to birth grits. Today, they stand as testaments to how food migrates, adapts, and heals,turning survival into identity.

In my own kitchen, straddling these worlds, I bridge the gap further. I prepare Southern-style cheese grits, then fold in Kenyan sukuma wiki: wilted collard greens sautéed with onions, tomatoes, and a hint of chili for that familiar tang. The result is a hybrid bowl creamy yet firm, spicy yet soothing that whispers of belonging. It is a reminder that home is not fixed; it is stirred together from the flavors that have shaped us, connecting the bayous of the South to the highlands of Kenya, one bite at a time.